Pharmacy Managers Unleash Big Data

Print

30 June 2016

Zachary Tracer / Bloomberd

OptumRx was doing a routine analysis of a client’s prescription-drug claims when it noticed something odd. The company’s spending on acne medicine seemed high compared with those of other customers. Digging into the usage data for clues, the pharmacy arm of the health insurer, UnitedHealth Group, found that employees had been prescribed newer brand-name acne drugs that were, for the most part, combinations of older generic medicines. OptumRx began requiring patients to begin treatment with the cheaper remedies and switch to the pricier ones only if the others proved ineffective. Within six months, the 60,000-employee company had saved more than $70,000, OptumRx says.

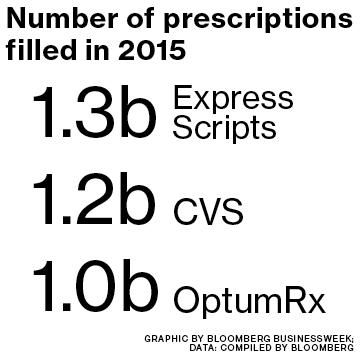

Historically, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have been known more for their relentless supply efficiency than their tech chops. But with the easiest savings already in the past, OptumRx and rivals such as CVS Health and Express Scripts have begun mining their huge troves of prescription data in search of economies. “Lowering costs now means having to make really difficult decisions about having to cover one drug vs. another,” says Walid Gellad, who heads the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh. “They’ve had to become more sophisticated in how they make these decisions.”

UnitedHealth began laying the groundwork for the data push in 2011, when it grouped an array of businesses under the Optum brand. In a recent case, the company noticed that at one client, drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were being overprescribed to adults. Some were using the drug to improve their performance at work, according to Andrea Marks, chief analytics officer at OptumRx. The benefit manager took action, saving the 19,000-worker company $110,000. “Sometimes we’re looking at patterns at a very broad-based level,” Marks says. “Sometimes at an individual level.”

As they seek to exert greater control over costs on behalf of their clients, PBMs may become more open to legal challenges. New York, Indiana, and West Virginia all passed laws this year to curb their influence over prescribing decisions in response to lobbying from patient groups. Sumit Dutta, OptumRx’s chief medical officer, says the company makes sure its coverage decisions are medically appropriate. “All of those have to be vetted clinically first,” he says. “You can’t say one drug is favored over another drug unless you’ve fully vetted that clinically.”

OptumRx says it’s also using data analytics to improve patient health. For example, it can look at refill frequency to spot whether asthma sufferers are taking too many puffs on their inhaler, an indication they may require a different drug. Switching patients to more effective medicines pays off, even if these are more expensive, if they help reduce costly hospitalizations and visits to emergency rooms.

Employers should be skeptical of claims like that, according to Linda Cahn, an attorney who’s represented businesses in lawsuits against PBMs. If benefit managers promise savings, those should be spelled out in contracts, she says.

The focus on Big Data dovetails with another development in the industry: Increasingly, insurers are tying reimbursements for prescription drugs to measures of their efficacy. Cigna, for instance, is paying for some new cholesterol drugs from Sanofi and Amgen/Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, known as PCSK9 inhibitors, based on whether the drugs deliver results at least as good as those reported in clinical trials.

There’s little doubt PBMs will use their data to gain the upper hand in price negotiations with drugmakers, says Dan Mahony, a health-care investor at asset manager Polar Capital. “They’re all looking at ways they can utilize the information they’ve got to essentially push for a better deal,” he says. “You’re just seeing the beginnings of it.”

All Portfolio

MEDIA CENTER

-

The RMI group has completed sertain projects

The RMI Group has exited from the capital of portfolio companies:

Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Syndax Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Atea Pharmaceuticals, Inc.