Broken Market for Old Drugs Means Price Spikes Are Here to Stay

Print

20 November 2015

Cynthia Koons, Robert Langreth / Bloomberg Business

With most products, you’d expect a flood of new supply to quickly drive back down a price spike caused by a temporary shortage. Not so in the topsy-turvy world of hospital pharmaceuticals.

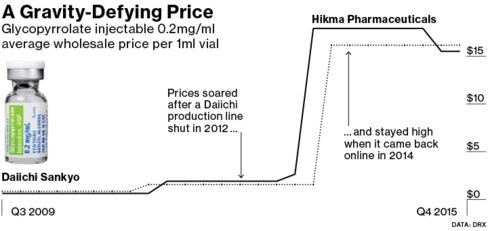

Just look at prices for glycopyrrolate, an everyday drug used to dry up secretions prior to surgery. After one of only two makers of the drug temporarily closed its factory in 2012 to fix quality control problems, Hikma Pharmaceuticals Plc raised prices on its injectable version more than 800 percent over the next year. Both manufacturers are now making the drug again, yet Hikma’s prices have only fallen slightly and remain more than eight times higher than they were in early 2013.

Glycopyrrolate is hardly an isolated case. All sorts of medications, from treatments for irregular heartbeats to supplies as basic as saline solution, have shot up in price as common hospital drugs are increasingly, and sometimes critically, in short supply. The reasons for the shortages are varied: creaky old factories, an FDA crackdown on quality control, companies exiting the market for more lucrative opportunities and fewer producers in the wake of a wave of mergers and acquisitions.

“It’s a broken market," said Stephen Schondelmeyer, a pharmacist and economist at the University of Minnesota who has studied drug prices. "Drug companies know there is going to be an end to this blank check era and they are pushing for whatever they can get."

Hikma said that higher prices helped cover the cost of increasing supply and shifting production to a new plant in Portugal after a supplier dropped out. After discounts, the drug still doesn’t cost more than $20 for a typical surgery, according to a company spokesperson.

Outpacing Inflation

Many in the industry maintain that massive price hikes on older drugs are limited to a few bad actors. Merck & Co. Chief Executive Officer Ken Frazier has said “companies that may take advantage of temporary market disruption to charge as much as they think the market will bear" behave in a way in a way that is “inappropriate.”

Still, some prices keep soaring. A survey conducted for Bloomberg News of 3,700 formulations of generic hospital drugs found more than 400 have at least doubled in price in the last eight years in the U.S., including about 50 that have gone up at least 10-fold. Roughly 25 percent of all old hospital drugs have gone up faster than the rate of inflation during that period, according to the survey of average wholesale prices by DRX, a unit of Connecture Inc. that provides price comparison software for health plans.

The price of procainamide, a drug from Pfizer Inc.’s Hospira used to treat irregular heartbeats, has jumped about 15-fold in the same period, according to DRX. Injectable papaverine, a blood vessel dilator that has only one manufacturer, has soared 700 percent in price in the U.S. in eight years.

Hospira said its manufacturing costs have increased substantially. It has invested more than $1 billion “to ensure high quality, life-saving medicines are available to patients in sustainable supply,” said MacKay Jimeson, a Pfizer spokesman.

Luitpold Pharmaceuticals Inc., a unit of Daiichi Sankyo Co. that also, along with Hikma, makes glycopyrrolate, said it invested in a successful factory renovation in 2012 where both drugs are manufactured. Papaverine price increases, over a longer time frame starting in 2003, were "less than half" the increase shown over eight years in the DRX numbers, according to the company.

Salt Water

Even increased demand for salt water -- saline solution -- has caused critical shortages, prompting four senators to ask the Federal Trade Commission to investigate “possible illegal collusion" by manufacturers Baxter International Inc., Hospira and B. Braun Medical Inc., according to an Oct. 26 letter from the senators. The letter said since the shortage started in late 2013, “suppliers are reported to have increased their prices by 200-300 percent.”

Baxter and B. Braun dispute the degree of the price increase. Baxter and Pfizer, which closed its acquisition of Hospira in September, said their drugs are fairly priced.

“The cost of this Baxter prescription product is less than a cup of coffee,” said William Rader, a spokesman for Baxter.

“Hospira responded by expanding its production of saline products to maximum capacity through manufacturing 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” said Pfizer’s Jimeson.

B. Braun is spending millions of dollars to increase capacity, said spokeswoman Constance Walker, who called the collusion allegation “ridiculous.”

To ease the saline shortage, the Food and Drug Administration gave the green light for temporary saline imports from overseas manufacturers, “something that we’ve had to do more and more in recent years” with a variety of drugs, said Valerie Jensen, associate director of the drug shortage staff at the FDA.

Fewer Competitors

Ironically, one important reason prices are soaring for generic hospital injectable drugs is that they have long been perceived as commodity, low-margin drugs without big money-making potential. So, one by one, manufacturers pull out until there are only one or two manufacturers who then have a free hand raising prices.

“There are very few companies that make these drugs," said Erin Fox, director of the drug information service at the University of Utah. “When you only have one or two suppliers of these products, sometimes three if you are lucky, one company may have large market share and if you have a glitch, you have a shortage."

During a shortage of drugs, prices go up, sometimes sharply, said John Lewin, director of the critical care and surgical pharmacy at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Once a shortage is resolved, while the price may ease slightly, it “never goes back to what it was.”

What’s more, the number of competitors for injectable drugs has continued to shrink, said Rena Conti, a professor of health policy and economics at the University of Chicago. The average number of makers for injected cancer drugs declined from 3.04 per drug in 2001 to 2.3 per drug in 2007, according to her recent analysis.

“Eventually you have one or two manufacturers left standing and they are monopolies in perpetuity,” she said.

Lone Manufacturer

That may explain why, even when there aren’t shortages, prices may rise. Cyclophosphamide, a half-century-old chemotherapy injection used to treat lymphoma and breast cancer, had only one manufacturer, Baxter, from late 2008 to late 2014. During that period, wholesale prices for the drug rose more than 1,200 percent, according to DRX.

Baxter’s U.S. sales soared to $463 million in 2014 from just $8 million in 2007, the last full year it shared the market with Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., according to IMS Health. In late 2014, another manufacturer, Novartis AG, entered the market. It says its list price is 10 percent lower than Baxter’s.

Baxter said it offers significant discounts off the drug’s list price even as demand has increased, and has spent $200 million since 2002 updating two factories in Germany. The medicine, moreover, only accounts for about 15 percent of costs for a lymphoma cocktail that includes four other drugs, said Laureen Cassidy, a Baxter spokeswoman.

Mergers are also reducing the number of suppliers in the broader generics market. Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., the biggest generics company, reached an agreement to buy the generics business of Allergan Plc in July. After acquiring Hospira, Pfizer’s in talks to acquire the remainder of Allergan.

Mitomycin’s Surge

The unpredictability of supplies is causing havoc in the marketplace. In 2012, Merck said it became the sole supplier of bladder cancer drug Tice BCG in the U.S. Merck CEO Frazier said the company kept its prices of BCG steady to continue offering the life-saving drug at a reasonable cost. But that didn’t prevent another bladder cancer drug, mitomycin, from soaring in price as BCG supplies ran low.

Since then, wholesale prices for mitomycin, which is now made by just one manufacturer, Accord Healthcare, have more than tripled to $1,415.64 for a 40-milligram vial, according to the data from DRX. Accord, a unit of India’s Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd., declined to comment.

The University of Utah’s Fox said the lack of information about suppliers make it impossible for hospitals to predict when prices are about to soar.

“There is just no transparency about who is making the drugs,” she said. “All the manufacturers have been operating at capacity, so one line going down can make a significant national shortage.”

All Portfolio

MEDIA CENTER

-

The RMI group has completed sertain projects

The RMI Group has exited from the capital of portfolio companies:

Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Syndax Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Atea Pharmaceuticals, Inc.