That Drug Coupon Isn’t Really Clipping Costs

Print

24 December 2015

Cynthia Koons, Robert Langreth / Bloomberg Business

“Free” copays spur sales of branded medicines, with insurers unhappily footing the bill.

When Valeant Pharmaceuticals International ran a TV ad after this year’s Emmy Awards broadcast featuring actor Mario Lopez promoting its new antifungal toe treatment, Jublia, the spot drew some barbs. But it’s also lured plenty of curious consumers who heeded the company’s invitation to visit the drug’s website for savings. There they found an online coupon that promised no out-of-pocket costs for eligible patients. That’s a great deal for consumers, because the prescription medicine costs more than $1,000 for an 8-milliliter bottle. It’s an offer many of their insurers would prefer to refuse.

Jublia’s marketing tack is part of a high-stakes game of chicken in which insurance companies raise copays on some drugs to as high as $100 to discourage their use, only to see pharmaceutical companies pick up the tab for those copays—seeking to leave insurers on the hook for the balance, often in the hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars per monthly prescription.

“It is a brilliant marketing strategy” on Big Pharma’s part, says Adriane Fugh-Berman, an associate professor of pharmacology and physiology at Georgetown University, who’s been a paid witness in lawsuits against some drug companies. She calls the practice an “insidious” way to circumvent insurance companies and employers who increasingly are trying to get patients to share the pain of soaring drug prices. Valeant didn’t respond to requests for comment.

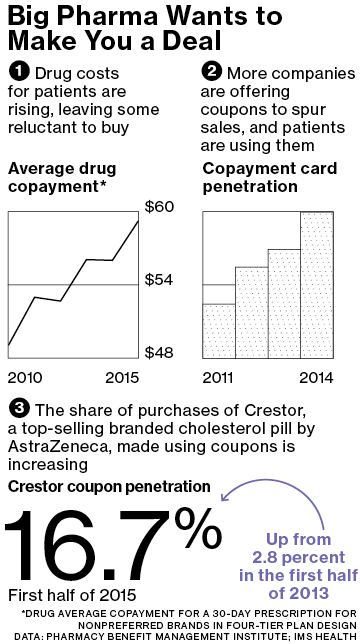

In 2015 the pharmaceutical industry will spend an estimated $7 billion—up from just $1 billion in 2010—to hand out coupons and discount cards to cover some or all patient copayments for drugs from fibromyalgia pain treatments to brand-name diabetes pills, according to data from IMS Health Holdings.

Research shows that the amount of money consumers have to shell out for pharmaceuticals affects their willingness to buy a medicine. When patients have a copay above $50, they’re more than four times as likely to abandon a prescription at the counter than when they have no copay, according to a 2010 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. The power to influence patient choices is one reason copay coupons are disallowed entirely in the federal Medicare program, where they’re considered an illegal inducement.

Drug companies say they’re just making the drugs more affordable for consumers. Patients could be stuck paying 20 percent or more of a drug’s price in the form of a copay, compared with about 7 percent of the cost of a physician visit or 4 percent of a total hospital bill, says Merck Chief Executive Officer Kenneth Frazier. “What we want to be able to do is help patients who need products and can’t afford to get them,” he says. “Coupons can be helpful in that sense.”

Holly Campbell, a spokeswoman for the trade group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, concurs. “Copay offset programs can play an important role in maintaining access to needed medicines, especially for patients taking specialty medicines or with chronic conditions,” she says. “Today, too many patients find that they are facing very high cost sharing that puts their ability to stay on a needed therapy at risk.”

Altruism aside, picking up copays is very good business for drug companies. Manufacturers can earn a 4-to-1 to 6-to-1 return on investment on copay coupon programs, according to the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents pharmacy benefit managers, the companies that manage drug plans for insurers and employers.

Copay coupons—which can be paper coupons, discount cards, or electronic codes used at pharmacies—are distributed through company websites, magazines, and doctors’ offices.

Insurance companies and the prescription benefits managers they work with are fighting back, dropping drugs from their plans. And consultant Dan Pollard, who started MyDrugCosts to consult with employers about lowering their health-care expenses, is developing a rewards program that would provide a cash incentive to patients who eschew coupons. “We’re changing the economics for the consumer,” he says.

Pharmacy benefit managers such as Express Scripts Holding and CVS Health have increased bans on some drugs, partly in response to the proliferation of coupon programs. Express Scripts will exclude about 80 drugs from its largest formulary in 2016. That’s up from 48 medicines in 2014. CVS will exclude about 120 drugs in 2016.

UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest health insurer, with about 46 million members, has been one of the industry leaders in combating copay coupons. In 2013 the insurer started blocking the acceptance of them for six expensive specialty drugs, including medicines for multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hepatitis C, according to consultant ZS Associates. Since then, UnitedHealth has expanded that no-coupon list to 35 specialty drugs, adding medicines for growth hormones, pulmonary hypertension, and infertility.

All the drugs have options that are more affordable, according to Lynne High, a spokeswoman for UnitedHealth. Manufacturer coupons “can drive patients away from lower-cost, therapeutically equivalent alternatives and can significantly increase overall health-care costs,” she says.

Studies have produced mixed results over whether the benefits coupons provided to consumers outweigh the higher costs they may incur. The coupons are most controversial when used for everyday drugs. One 2013 analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 62 percent of coupons studied were for brand-name drugs for which lower-cost alternatives were available. Older medicines to treat toe fungus, for example, can be had for $30 or less, a fraction of today’s new branded prescription remedies.

When low- or no-copay promotions are used for very expensive specialty drugs, though, such as medicines for rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis that can cost $2,500 a month or more, a 2014 study in Health Affairs found, coupons reduced a consumer’s share of the drug cost to less than $250—and usually much less. That’s low enough that patients were more likely to continue taking needed prescriptions.

For pharmacists who’ve seen the discount cards and coupon programs proliferate over the years, the punch-counterpunch between insurers and drugmakers seems like more trouble than it’s worth. “These cards are put out to level the playing field for the consumer,” says Andy Miller, an independent pharmacist in Brattleboro, Vt. “We’re creating systems within systems. Maybe drug companies should just lower the pricing.”

The bottom line: The pharmaceutical industry will spend an estimated $7 billion this year on coupons to offset insured patients’ copays for their drugs.

All Portfolio

MEDIA CENTER

-

The RMI group has completed sertain projects

The RMI Group has exited from the capital of portfolio companies:

Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Syndax Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Atea Pharmaceuticals, Inc.