How Big Pharma Uses Charity Programs to Cover for Drug Price Hikes

Print

20 May 2016

Benjamin Elgin / Bloomberg

In August 2015, Turing Pharmaceuticals and its then-chief executive, Martin Shkreli, purchased a drug called Daraprim and immediately raised its price more than 5,000 percent. Within days, Turing contacted Patient Services Inc., or PSI, a charity that helps people meet the insurance copayments on costly drugs. Turing wanted PSI to create a fund for patients with toxoplasmosis, a parasitic infection that is most often treated with Daraprim.

Having just made Daraprim much more costly, Turing was now offering to make it more affordable. But this is not a feel-good story. It’s a story about why expensive drugs keep getting more expensive, and how U.S. taxpayers support a billion-dollar system in which charitable giving is, in effect, a very profitable form of investing for drug companies—one that may also be tax-deductible.

PSI, which runs similar programs for more than 20 diseases, jumped at Turing’s offer and suggested the company kick things off with a donation of $22 million, including $1.6 million for the charity’s costs. That got Turing’s attention. “Did you see the amounts??? $22MM!!!” wrote Tina Ghorban, Turing’s senior director of business analytics, in an e-mail to a colleague. (The document was obtained by congressional investigators looking into the company’s pricing.) Turing ultimately agreed to contribute $1 million for the patient fund, plus $80,000 for PSI’s costs.

PSI is a patient-assistance charitable organization, commonly known as a copay charity. It’s one of seven large charities (among many smaller ones) offering assistance to some of the 40 million Americans covered through the government-funded Medicare drug program. Those who meet income guidelines can get much or all of their out-of-pocket drug costs covered by a charity: a large initial copay for a prescription, another sum known as the coverage gap or the donut hole, and more-modest ongoing costs. It adds up fast. After Turing raised Daraprim’s price, some toxoplasmosis patients on Medicare had initial out-of-pocket costs of as much as $3,000.

That’s just a fraction of the total cost. Turing’s new price for an initial six-week course of Daraprim is $60,000 to $90,000. Who pays the difference? For Medicare patients, U.S. taxpayers shoulder the burden. Medicare doesn’t release complete data on what it pays pharmaceutical companies each year, but this much is clear: A million-dollar contribution from a pharmaceutical company to a copay charity can keep hundreds of patients from abandoning a newly pricey drug, enabling the donor to collect many millions from Medicare.

The contributions also provide public-relations cover for drug companies when they face criticism for price hikes. An internal Turing case study about how to talk about price increases, written last October and released by Congress earlier this year, contained the suggestion that patient assistance programs be “repeatedly referenced.”

“It looks great for pharmaceutical companies to say they are helping patients get the drugs,” says Adriane Fugh-Berman, a doctor who’s studied pharma marketing practices for three decades and is an associate professor of pharmacology and physiology at Georgetown University. The intent of these donations, she says, is to “deflect criticism of high drug prices. Meanwhile, they’re bankrupting the health-care system.”

It’s not just Daraprim. In 2014, the drug company Retrophin—run at the time by Shkreli—acquired Thiola, a 26-year-old drug that treats a rare condition in which patients constantly produce kidney stones. As Retrophin raised the drug’s price 1,900 percent, it also gave money to PSI for copay aid for kidney-stone patients. In 2010, Valeant Pharmaceuticals International bought a pair of old drugs that treat Wilson Disease, an obscure disorder in which copper accumulates in the body. Three years later, amid a series of price increases that ultimately exceeded 2,600 percent, Valeant gave money to the Patient Access Network (PAN) Foundation for copay aid to Wilson Disease patients.

Fueled almost entirely by drugmakers’ contributions, the seven biggest copay charities, which cover scores of diseases, had combined contributions of $1.1 billion in 2014. That’s more than twice the figure in 2010, mirroring the surge in drug prices. For that $1 billion in aid, drug companies “get many billions back” from insurers, says Fugh-Berman.

“Drug companies aren’t contributing hundreds of millions of dollars for altruistic reasons,” says Joel Hay, a professor and founding chair in the department of pharmaceutical economics and policy at the University of Southern California. The charities “don’t ever have to scrounge for money. It falls right to them.” Both Hay and Fugh-Berman have served as paid expert witnesses in lawsuits against drug companies.

When Turing bought Daraprim and sought to boost its annual revenue from $5 million to more than $200 million, the use of patient-aid funds was considered essential, internal company documents show. Last May, as the company did its due diligence before the purchase, one executive warned in an e-mail that new, high copays would force toxoplasmosis patients to seek alternative drugs.

“We want to avoid that situation,” wrote Nancy Retzlaff, Turing’s chief commercial officer. “The need to address copay assistance is a key success factor.” Turing officials declined an interview request but said in an e-mail that by “success,” Retzlaff meant that “no patient is denied access to our medicines by inability to pay.” Turing added that it gives hospitals discounts of up to 50 percent on Daraprim and that most patients receive the drug through programs such as Medicaid that pay just 1¢ per pill.

Nonetheless, a document in which PSI laid out its plans for the new fund contained a clue about whose interest was being served. It says: “Client | Turing Pharmaceuticals.”

In 1983, Dana Kuhn was a young man working in a Presbyterian church in Jackson, Tenn., when his life took a tragic turn. During a fundraising basketball game, he went up for a rebound, came down awkwardly, and broke his foot. A mild hemophiliac, Kuhn received a blood infusion. It contained the HIV virus. Not realizing he was infected, Kuhn transmitted the virus to his wife, who died in 1987, leaving him the sole parent of their two young children.

Kuhn became an advocate for hemophilia patients and a plaintiff in a lawsuit against drug companies that were slow to address the risk of HIV in clotting treatments. He also began working as a counselor to hospital patients, and in that capacity he saw how medical costs harmed families, even those with insurance. Patients blew through their savings; some had to sell their homes, he recalls.

He founded PSI from his kitchen table in 1989 and ran it without drawing a salary for the first seven years. “The right kind of assistance can keep somebody in their home, help them maintain a job, and keep them as a productive member of society,” says Kuhn, now a lanky 63-year-old with close-cropped brown hair and a graying mustache.

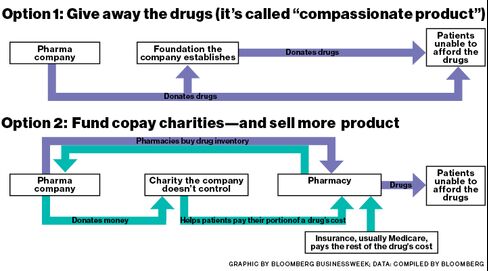

Kuhn created the model, and an act of Congress in 2003 allowed such charities to dramatically expand in scale. That year, lawmakers expanded Medicare, creating Medicare Part D to cover prescription drugs. This big, taxpayer-funded market came with a catch for drugmakers: They’re allowed to give direct help to patients covered by commercial insurers—and discount cards covering drug copays have become ubiquitous—but they can’t do the same for Medicare patients. Direct gifts to these people can be considered illegal kickbacks, improperly steering patients to a particular company’s drug instead of cheaper alternatives.

However, government policy does allow “bona fide, independent” charities to help Medicare patients with drug costs. Pharma companies can contribute to charities for specific diseases, provided they don’t exert any sway over how the nonprofits operate or allocate their funds.

Under the new rules, PSI’s revenue grew rapidly, from $16 million in 2003 to $128 million last year. In 2014 the charity said just over half its funds came from a single drug company, though it didn’t name the donor. Former employees say it was Novartis; Novartis confirmed it’s given to PSI, but declined to say how much.

The largest copay charity, the PAN Foundation, grew even faster, soaring from about $36 million in contributions in 2010 to more than $800 million last year. About 95 percent of PAN’s contributions come from the pharma industry, the charity says; in 2014, five unnamed drug companies kicked in more than $70 million apiece, according to PAN’s tax filing. With this eager stable of donors, PAN spent just $597,000 on fundraising in 2014. That’s less than 1 percent of the fundraising expense for similar-sized charities, like the American Cancer Society and the American Heart Association.

Kuhn’s compensation has increased along with PSI’s scope. In 2014 his salary was $576,000, making him the highest-paid copay charity executive. Kuhn has also had close business dealings with the charity he created. Before 2004, PSI contracted out some of its operations, including fundraising and program services, to a for-profit company called Managed Care Concepts, which Kuhn co-owned. The charity also leased office space from Kuhn’s company. In 2005 the charity purchased office buildings from Managed Care Concepts for $1.06 million, or about $200,000 more than the company had paid for them in 2000 and 2003.

During that time, PSI also paid Kuhn $476,000 for intellectual property that was “vital to the ongoing activities of the organization,” according to the charity’s tax filings. The IP in question is an Excel spreadsheet that helps calculate how much aid patients should get, according to six former employees and managers at PSI. (In a written statement, the charity defends Kuhn’s compensation as being commensurate with his experience. The price increase on the buildings purchased from Kuhn’s company was in line with the shifting real estate market, it says. And the spreadsheet was valued at nearly 10 times the amount Kuhn received for it by a firm hired by PSI’s board.)

Kuhn talks about PSI only until he’s asked about the Turing donation. Then his tone grows fierce. “I want to make sure you’re not getting into a situation here where a patient dies because of what you write,” he says. “What goes around comes around. Don’t continue to shovel dirt onto patients. The foundations, we’re just trying to throw out lifejackets to people who were on the Titanic. Everyone else is trying to throw debris on the patients to sink them. It’s just cruel.”

“I’d be dead without PSI,” says Steve Ashbrook, a retired optician in Cincinnati. He was diagnosed in 2009 with chronic myeloid leukemia, or CML, a slow-moving cancer that starts in the bone marrow. His doctor prescribed Gleevec, a Novartis drug that’s helped double CML patients’ five-year survival rate, to 63 percent, since the 1990s.

When Ashbrook started on Gleevec, he was on a high dose that cost $6,000 per month. Ashbrook, who lives on $1,600 per month from Social Security, was facing initial out-of-pocket costs of more than $2,000, and $300 a month after that. At first, Novartis gave him free medicine, as drugmakers often do for patients who can’t afford it. The industry has a term for that: “compassionate product.” Ashbrook’s doctor told him about PSI, and a month or two after starting on Gleevec, Ashbrook qualified for help. PSI began covering his out-of-pocket costs while his Medicare plan paid the rest.

Ashbrook says he couldn’t care less where PSI’s money comes from. That’s presumably true of most of the hundreds of thousands of patients supported by copay charities—they’re just grateful for the help. But Ashbrook’s story illustrates how the system enables drug pricing that squeezes Medicare.

A year’s supply of Gleevec can be produced for less than $200, according to Andrew Hill, a researcher at the University of Liverpool. When the drug was introduced, in 2001, its U.S. price was $30,000 a year. At that level, it would have recouped its development costs in just two years, according to a letter from 100 cancer specialists, published in the medical journal Blood in 2013. The price is now up to $120,000 a year in the U.S. (It’s priced at drastically different rates around the world: $25,000 a year in South Africa, for example, and $34,000 a year in the U.K.)

As Gleevec’s price has climbed, so has the burden on taxpayers. Medicare spent $996 million on the drug in 2014, up 158 percent from 2010. Most of that increase is the result of price hikes; Gleevec’s U.S. list price jumped 83 percent from January 2010 to January 2014, from $139 to $255 per 400-milligram pill. (A generic is expected to lower costs in the future.)

Eric Althoff, a spokesperson for Novartis, said via e-mail that the company’s pricing isn’t, and shouldn’t be, based on the cost of developing and manufacturing its drugs. “We invest in developing novel and current treatments to find ways to make more cancers survivable,” he said. “This is challenging and risky and needs to be taken into consideration when discussing pricing of treatments.” Althoff also said Novartis had contributed $389.4 million to copay charities since 2004.

The charities are at pains to distance their work from the drugmakers’ pricing strategies. “Pharmaceutical companies do want to donate to nonprofits to help people,” says Kuhn. “For what reasons? I can’t answer that.”

Daniel Klein, PAN Foundation’s chief executive officer, says his organization has no influence over drug prices. “We are unaware of any data demonstrating that the help provided by charitable patient assistance organizations such as PAN has any impact on drug prices,” he says. In interviews and e-mails, the heads of several other copay charities also stressed their independence from donors.

If a charity fund pays mostly for one particular drug, it may be for reasons that have nothing to do with whether the drug’s maker is a donor—one drug might simply have a bigger market share, for example. If, however, a charity supports one drug over another when both treat the same disease, that could violate Medicare’s anti-kickback rules. The criminal penalties for such violations can reach $25,000 and five years in prison for each kickback, and civil fines can be up to $50,000 per violation.

To ensure that charities and drug companies operate independently, federal regulators prohibit the charities from disclosing detailed information about their operations, which drug companies could use to calculate the impact of their donations to their bottom lines. However, data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act shows that pharma companies are able to sponsor funds that mostly support their own drugs. Over a 16-month period in 2013 and 2014, PAN Foundation had 51 disease funds, 41 of which got most of their money from single drug-company donors, according to data PAN provided to regulators. Of those 41, 24 funds paid most of their copay assistance claims for patients using drugs made and sold by their dominant donor.

PAN’s Klein says all its funds are managed “in strict compliance with federal regulations and all are managed independently of the donors.” Charity directors say they try to have their funds cover wide varieties of medicines, lessening the chance that a drugmaker can support mostly its own customers. “In our model, the money gets spread out across a lot of different treatments and products,” says Alan Balch, CEO of the Patient Advocate Foundation, which counsels patients and also has a copay program.

But in presentations and marketing materials over the years, some charities have explicitly pitched drug companies on how donations can help their bottom lines. In a PSI newsletter in 2004, Kuhn promised a “win-win” solution for patients and drugmakers. “We provide a way for pharmaceutical companies to turn their ‘free product’ programs into revenue by finding long-term reimbursement solutions,” he wrote. Even today, on the PSI website, one executive describes how companies working with the charity “have realized increased product usage” while reducing “use in compassionate product.”

Another charity, Chronic Disease Fund, was even more explicit. In a brochure published in 2006, it said drugmakers’ gifts to copay charities—which, again, may be tax-deductible—can be more profitable than many of the companies’ for-profit initiatives. “In other words,” the CDF pamphlet said, “to achieve the same return as your charitable patient financial assistance program you would need to run a pre-tax for-profit program with a return of 81 percent.”

CDF now goes by the name Good Days from CDF. It changed its moniker after the copay charities endured the closest thing they’ve ever seen to a scandal. In 2013, Barron’s published an article suggesting CDF was creating disease funds to help Questcor Pharmaceuticals, a drugmaker that was donating millions of dollars to the charity. CDF was offering assistance to people afflicted with 37 diseases, but eight of its funds supported only a single Questcor product called Acthar, according to Barron’s. Acthar treats a range of ailments from infantile spasms to lupus, but other treatments for those maladies are available. After additional publicity, including a couple of detailed reports from short sellers, who suggested Questcor’s sales were propped up by an improperly close relationship with the charity, CDF replaced its top executive and board of directors.

CDF “completely disavows” the 2006 brochure, says Jeffrey Tenenbaum, an attorney for the charity and a partner at law firm Venable. He says the brochure hasn’t been used in a decade and “is completely inconsistent with every policy and position that the organization takes.” He adds that there was nothing improper with the Questcor relationship and that there’s nothing wrong, in general, with drug companies benefiting from these charities, if their contributions are necessary to help patients. “Of course there are benefits to drug companies, but the benefits to the general public are greater,” says Tenenbaum.

The Department of Health and Human Services responded to the CDF flap by telling all nonprofits in 2014 that it was going to scrutinize disease funds more closely to make sure they weren’t favoring drug-company donors. Since then, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) at Health and Human Services, which oversees Medicare spending, has largely signed off on the operations of most of the charities.

In December the inspector general gave a favorable advisory opinion to Caring Voice Coalition, a charity that attracted $131 million in contributions last year. Five former managers and employees say Caring Voice favored drug companies that were donors over those that weren’t. Patients who needed donor companies’ drugs got help quickly, the former staff members say, while patients who had the same disease but used another company’s drug were sometimes steered away or wait-listed. The former employees asked that their names not be used because they signed nondisclosure agreements or they feared backlash from the charity’s executives.

In 2011, Caring Voice set up a fund for narcolepsy, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals made a donation. Jazz makes the narcolepsy drug Xyrem, which has risen in price by more than 1,000 percent since 2007 and now costs about $89,000 per year for a typical patient, according to Connecture, which sells software that compares drug prices. Two other drugs that treat narcolepsy, Provigil and Nuvigil, were made at the time by a company called Cephalon, which wasn’t a Caring Voice donor. When narcolepsy patients contacted Caring Voice, those who used Xyrem could typically expect help quickly, the former employees say. Patients who used Provigil or Nuvigil were referred back to Cephalon. Patients who could prove that Cephalon’s foundation denied them help would be added to a Caring Voice waiting list. One former manager says he doesn’t recall anyone moving off the wait list and getting help.

On May 10, Jazz Pharmaceuticals announced that the Department of Justice had issued a subpoena for documents related to the company’s support of charities that provide financial assistance for Medicare patients. The Jazz disclosure specifically mentioned Xyrem but didn’t provide details about which relationships with specific charities were under scrutiny. The company declined to comment about the subpoena.

It’s unclear how much money Jazz contributed to Caring Voice, but a company spokeswoman confirmed it has given since 2011 and said the company has no role in determining which patients the charity supports. In an e-mailed statement, Caring Voice’s president, Pam Harris, said the nonprofit’s programs cover a broad variety of drugs and its staff members use uniform criteria to determine patients’ eligibility for help, regardless of which drugs they use. “Assistance is awarded without regard to any donor’s interest,” Harris said. She declined to answer additional questions.

One panel discussion focused on “OIG oversight” and “opinions and developments on patient assistance.” Another focused on “legal and compliance considerations.” A third touched on “manufacturer/foundation relations.” Bloomberg Businessweekwasn’t allowed to hear what was said; at the check-in desk, a conference staffer told a reporter that journalists weren’t welcome at the two-day event, even if they paid the $2,399 entrance fee.

In the hotel lobby, Kuhn, the father of this industry, sat alone, eating a light breakfast. He was wary of answering more questions and demurred on a request to visit PSI’s offices. He asked for a guarantee that a story wouldn’t damage the system he built. The charities, Kuhn said, “are all totally legitimate.” On the phone, weeks earlier, he’d expressed a similar concern. “I don’t want to see people put uneducated questions into people’s minds about not-for-profit foundations,” Kuhn said.

If the government forced charities to expand their funds to include multiple diseases and more drugs, pharma companies might pull their support, he said. “Some foundations might have to close programs because they become so broad.”

Is that because drug companies won’t support charities if they can’t be sure they’re also helping themselves?

“Of course,” Kuhn said. “We live in a capitalistic society. Everyone needs to make a little bit of money.”

All Portfolio

MEDIA CENTER

-

The RMI group has completed sertain projects

The RMI Group has exited from the capital of portfolio companies:

Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Syndax Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

Atea Pharmaceuticals, Inc.